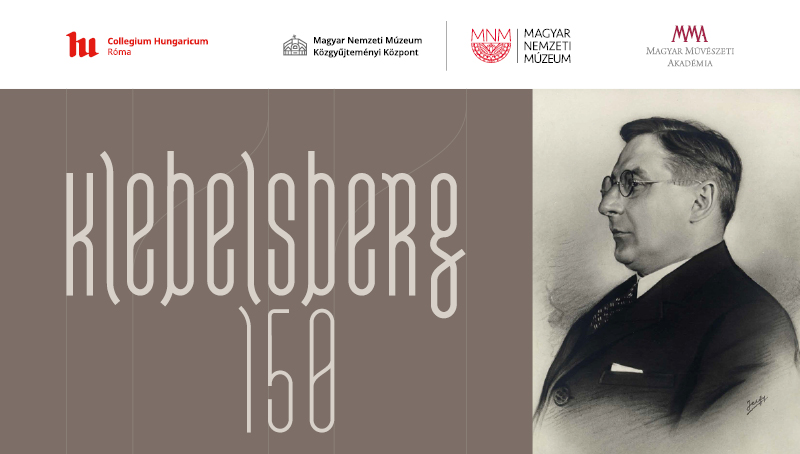

Klebelsberg 150

In 2025, Hungary commemorates the 150th anniversary of the birth of Count Kuno Klebelsberg, Hungary's Minister of Religion and Public Education.

Klebelsberg was a highly knowledgeable, influential, and outstanding figure in Hungary's history following World War I.

As minister, he ensured that his department received an increasing share of the Hungarian state budget year after year. By the 1928/1929 fiscal year, an impressive 10% (!) of the national budget was allocated to cultural affairs. As a result of his decade-long ministerial work, Hungarian cultural life began to flourish.

His investments led to significant developments, ranging from primary education institutions to universities. He was convinced that "the Hungarian homeland... can be preserved primarily not by the sword, but by culture."

Our exhibition presents an overview of Klebelsberg's life and ministerial achievements.

Picture(s):

Count Kuno Klebelsberg, Hungary's Minister of Religion and Public Education | Photo by Gyula Jelfy, Budapest, around 1930

Team of Experts of the Hungarian National Museum:

Concept: Lajos Sóti, Image selection and text: Lajos Sóti, Beatrix Lengyel

Language Editor: Ágnes Merényi, Project Manager: Samira Kebiche

Graphics and adaptation: Péter Gajdács, Afrodité Alajbeg

The artefacts belong to the collection of the Hungarian National Museum

THE BEGINNING

Kuno Klebelsberg was born on 13 December 1875 in Magyarpécska (now: Pecica, Romania) as the child of cavalry captain Jakab Klebelsberg and Aranka Farkas. The male members of the Tyrolean family have distinguished themselves with their bravery, especially on Hungarian battlefields against the Ottomans, for which the family earned a baronial title in 1669 and a countly rank in 1702.

After the early loss of his father, he was raised by his grandfather, and following his grandfather's passing, his uncle became his guardian. He completed his primary and secondary education in the ancient Hungarian coronation city of Székesfehérvár. In 1898, he obtained his law degree from the University of Budapest.

Picture(s):

1 Kuno Klebelsberg as a child | Photograph by Antal Pribék, Székesfehérvár, 1878

2 Klebelsberg with his uncle, who became his guardian after 1882 | Photograph by István Szigeti, Székesfehérvár, between 1882 and 1885

3 Klebelsberg, the young Secretary of State (second from the right) at a tea reception hosted by Prime Minister István Tisza and his wife at the residence in Buda Castle | Photograph by Gyula Jelfy, 1914

KLEBELSBERG'S CULTURAL POLICY

Following the Treaty of Trianon, which concluded World War I, Hungary suffered significant territorial losses and became diplomatically fully isolated. About half of the Hungarian-speaking population was transferred to neighbouring countries. Therefore from the moment of his appointment on 16 June 1922, Klebelsberg sought to break free from this situation.

His work was built on two fundamental pillars. Firstly, he aimed to raise the cultural standards of all groups within Hungarian society by developing public education at every level. Secondly, he focused on elite education, strengthening scientific institutions and establishing Hungarian research institutes abroad. In implementing his vision, he relied on two key colleagues: Zoltán Magyary, a pioneering university professor and the establisher of the cultural public administration system, and Gyula Kornis, a Piarist monk who first served as his educational advisor and later as his state secretary.

Picture(s):

1 Klebelsberg planning the cultural budget. with the Minister of Finance in the background attempting to prevent him | Caricature by László Madaras, 1927

2 Zoltán Magyary | National Press Portrait Service, Budapest, 1941

3 Gyula Kornis | Photograph by Aladár Székely, Budapest, 1935

4 Kuno Klebelsberg in the library of his Budapest villa | Photograph by Gyula Czvek, 1931

PUBLIC SCHOOL PROGRAM

Klebelsberg launched the public school program in 1926 with the aim of raising the educational level of the widest segments of society. The country was divided into zones with a 5 km radius, and local authorities or landowners were required to establish public schools.

As a result 5,000 public school were built by 1930. Klebelsberg's plans included raising the compulsory school age to 14, but this measure was only implemented after his death in 1940. As a result of public school education, the number of illiterate people decreased by one-third between 1920 and 1930, dropping from 15.2% to 9.6%. By 1935, only 7% of the Hungarian population remained illiterate.

Picture(s):

1 Opening ceremony of an elementary public school in Kispest. The importance of elementary schools was highlighted by Klebelsberg's frequent personal attendance at inauguration ceremonies. | Photograph by Hauser's Successor Studio, 1926

2 Arithmetic class at the St. Margaret Girls' School in Buda | Photograph by István Szendrő, 1930s

3 A typical Great Hungarian Plain school building with the teacher's residence in the background in Domaszék. This school was named after Klebelsberg | Photograph by an unknown photographer, second half of the 1920s

4 A natural history class at the middle-class boys' school in Battonya | Photograph by Antal Werner, 1930

SECONDARY SCHOOLS

Klebelsberg advocated for a more practical curriculum and the teaching of modern foreign languages in secondary schools. As a result, in 1924, he introduced a new type of school, the modern secondary school („reálgimnázium"), which served as a transition between the classical secondary school („gimnázium") and the technical school („reáliskola").

In classical secondary schools, humanities and Latin remained dominant, while technical school institutions focused on practical subjects. The newly established modern secondary school placed emphasis on science and technical subjects. In 1926, girls' education was also restructured into a similar three-tier model: girls' grammar school, girls' lyceum, girls' college. Both boys' and girls' secondary schools provided a high level of education and a solid foundation of knowledge.

Picture(s):

1 Girls gathered around a demonstration skeleton in the corridor of the Szent Margit Girls' Grammar School in Budapest | Photograph by István Szendrő, 1932

2 Drinking fountain in a grammar school | Photograph by an unknown photographer, around 1930

3 Swimming instruction at the St. Margaret Girls' Grammar School in Budapest | Photograph by István Szendrő, 1932

HIGHER EDUCATION

At the beginning of Klebelsberg's term as Minister of Culture only two universities remained within the borders of Hungary as a result of the Treaty of Trianon: in Budapest and Debrecen. Klebelsberg organized the relocation of the universities of Pozsony (today: Bratislava) and Kolozsvár (today: Cluj) to within the country's borders, with the former moving to Pécs and the latter to Szeged.

The renowned Mining and Forestry Academy of Selmecbánya (today: Banská Stiavnica) moved to Sopron. In addition to university education Klebelsberg considered physical training and education to be of great importance, therefore in 1925, he founded the University of Physical Education in Budapest. Alongside training physical education teachers, coaching education was also offered there.

Picture(s):

1 Minister Kuno Klebelsberg signs the founding charter of the Szeged University Clinic | Photograph by unknown photographer, 5 October 1926

2 Fencing class at the University of Physical Education in Budapest | Photograph by unknown photographer, 1925

3 The minister among the attendees at the opening ceremony of the Budapest University of Education (raising his hat) | Photograph by unknown photographer, 1927

PUBLIC COLLECTIONS

The National Institution of Hungarian Collections was established to coordinate the work of public collections and optimize their financing. The institutions integrated into the organization – the National Archives, the Hungarian National Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, the Museum of Applied Arts, and the University Library – formed a joint self-governing council under the minister's leadership, composed of representatives from these institutions and other elected members.

Thanks to the council's autonomy, it managed independently the collections under its authority. The first step was to harmonize the staff's assignments and salaries. Later, additional collections joined the organization.

Picture(s):

1 The building of the National Archives. Klebelsberg did everything in his power to complete the construction, which had started before World War I. The building was inaugurated in 1923| Photograph by an unknown photographer, Budapest, 1930

2 Klebelsberg, the Minister of Culture | Drawing by Lajos Márton, 1931

3 Council meeting of the National Institution of Hungarian Collections. Minister Klebelsberg, accompanied by the directors general of the National Archives, the Museum of Applied Arts and the secretary of the organization | Photograph by Mór Eiser (?), 1931

4 Lajos Kossuth memorial exhibition in the National Museum belonging to the National Institution of Hungarian Collections | Photograph by unknown photographer, 1924

THE NATIONAL MUSEUM DURING KLEBELSBERG'S MINISTRY

The development and reconstruction of the building housing the national collections began in the 1920s. The visitor area was enlarged, the benches originating from the former Upper House of Parliament were removed from the ceremonial hall. New storage space was created by incorporating the upper floor. From 1923 onwards, Klebelsberg's successor, historian Bálint Hóman, led the museum.

In the final years of Klebelsberg's ministry, the museum garden was enriched with new artworks. In 1929, during a ceremony honouring Colonel Alessandro Monti, the leader of the Italian Legion who participated in the Hungarian War of Independence of 1848-1849, the City of Rome presented a gift: a column from the Temple of Peace in the Forum Romanum, along with a bust of Monti created by the sculptor Lívia Kuzmik, scholarship recipient in Italy. The following year, a statue of the renowned Hungarian naturalist, Ottó Herman, was added to the garden.

Picture(s):

1 The Rotunda of the Hungarian National Museum, in the middle the floor mosaic of a Roman villa excavated in Baláca in the former province of Pannonia | Photograph by unknown photographer, 1926

2 Prime Minister Count István Bethlen lays a wreath in front of the Forum Romanum column in the Museum Garden | Photograph by the Hungarian Film Office, Budapest, 1929

3 Bálint Hóman, director of the National Museum | Photograph by István Zubor, 1937

4 The new decorative lighting of the National Museum after the reconstruction | Photograph by unknown photographer, 1926.

COLLEGIUM HUNGARICUM

During Klebelsberg's ministry, the Collegium Hungaricum institutions were established, to serve as strongholds of Hungarian culture abroad. The system had two predecessors. One was the Hungarian Historical Institute in Rome, founded by Bishop Vilmos Fraknói. The bishop used his own income to provide research opportunities for Hungarian historians of the era in the Vatican's Secret Archives, which had been opened by Pope Leo XIII.

The other was the Hungarian Scientific Institute in Constantinople, established in 1917 at the suggestion of the Hungarian Historical Society at the beginning of Klebelsberg's presidency. This short-lived institute was headed by Antal Hekler, a classical philologist and archaeologist, a researcher of Roman portraiture, and one of the founders of Roman provincial art studies.

The system of Collegium Hungaricum institutions, which ensured Hungarian researchers a stable, long-term research environment through scholarships, as well as study trips for artists, was granted legal protection. In 1927, the law provided for the institutes in Vienna, Berlin, and Rome.

Picture(s):

1 The Fraknói Villa in Rome, the headquarters of the Hungarian Historical Institute in Rome. Today, it houses the Hungarian Embassy next to the Holy See. | Gyula Háry, late 19th century

2 Vilmos Fraknói, titular bishop, historian, secretary general of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences | Photograph by unknown photographer, 1924

3 Antal Hekler, classical archaeologist, member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences | Photograph by unknown photographer, 1940

COLLEGIUM HUNGARICUM, VIENNA

The establishment of the Collegium Hungaricum in Vienna can be traced back to the centuries-old shared history of the two nations. After World War I, the official Hungarian-related documents and numerous artifacts of the former Austro-Hungarian Monarchy remained in the former imperial city.

To search for these, the Hungarian Historical Society, of which Klebelsberg was the president, launched a mission in 1920 at the Haus-, Hof-, und Staatsarchiv. The mission was housed in the former palace of the Hungarian Royal Guard in Vienna, which later served as the building for the Collegium Hungaricum for decades. During Klebelsberg's ministry, Vienna hosted the largest number of scholarship holders, mostly historians and university students specializing in German.

Picture(s):

1 The former building of the Collegium Hungaricum in Vienna | Photograph by Kálmán Szöllősy, 1930s

2 The dining room of the Collegium Hungaricum in Vienna | Photograph by Bruno Reiffenstein, 1920s

3 Prime Minister Count István Bethlen visiting the Collegium Hungaricum | Photograph by unknown photographer, Vienna, 1931

COLLEGIUM HUNGARICUM, BERLIN

The history of the Hungarian Institute in Berlin and the system of Collegium Hungaricum is closely intertwined with the life work of the Germanist Robert Gragger. In the last years of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, in 1916, Gragger established the Hungarian Department at Humboldt University. This Berlin-based department was the first Hungarian department abroad. Gragger coined the term Hungarology and was the discoverer of the first Hungarian poem preserved in the so-called Leuven Codex, the earliest surviving lyrical work of the entire Finno-Ugric language family.

In addition to his scholarly work, he was one of the most prominent Hungarian cultural diplomats, known for his extraordinary organizational skills. In 1923, under Gragger's leadership, the Hungarian state purchased the first building for the Collegium Hungaricum in Berlin, located on Marienstrasse. By 1924, the scholarship holders, whom he considered his family, were able to move in. Unfortunately, Gragger did not live to see the full fruition of his work, passing away in 1926 at the age of just 39.

In Berlin, study opportunities were primarily provided for German-speaking teachers, Protestant theologians, and students of law and political sciences.

Picture(s):

1 Róbert Gragger, around 1925 | Photograph by an unknown photographer

2 A room at the Collegium Hungaricum in Berlin | Unknown photographer, 1920s

3 Prime Minister Count István Bethlen at a reception at the Collegium Hungaricum in Berlin | Unknown photographer, 1930

HUNGARIAN ACADEMY, ROME

The predecessor of the Hungarian Academy in Rome was the Roman Hungarian Historical Institute, founded in 1895 by Bishop Vilmos Fraknói. The private institute hosted scholarship recipients for a decade, and in 1922, it was brought under state funding. In, 1927, following an agreement between the Italian and Hungarian governments regarding the transfer of the building, the institute moved to the Falconieri Palace, designed by Francesco Borromini.

Unlike the other two Collegium Hungaricum institutions, the name of this one was suggested by its director, art historian Tibor Gerevich. He argued that the term "collegio" in Italian might be misleading. The Hungarian Academy in Rome primarily hosted church historians, and, thanks to the scholarships introduced in 1928, artists. From the work of these artists, one of the defining movements of Hungarian art emerged—the Roman School, the Hungarian variant of Italian Neoclassicism.

Picture(s):

1 Rome, Via Giulia | Painting by Ödön Bartus, circa 1930

2 The living room of a fellow at the Hungarian Academy in Rome | Photograph by unknown photographer, circa 1925

3 Tibor Gerevich, the life-loving art historian and the main driving force behind Italian-Hungarian relations. | Photograph by unknown photographer, circa 1930

CORVIN AWARDS

In 1930, at Klebelsberg's suggestion, the Corvin Awards were introduced to recognize outstanding contributions to Hungarian science, literature, art, and public education. The Corvin Chain and Corvin Wreath were awarded to the most distinguished personalities of the era, who came from diverse intellectual and political backgrounds, with the first awards presented in 1931.

The recipients of the awards formed a body that also decided on the new laureates. The Badge of Honour was intended to honour foreigners, and a total of six were awarded, including two Italians: Giuseppe Bottai, Minister of National Education, and Amadeo Giannini, a senator. The only special grade of the award, the Gold Badge the Hungarian Corvin Chain with a gold star, was conferred upon King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy for his numismatic activities. In 2001, the Corvin Chain award was re-established and is now the highest state recognition in Hungary, second only to the Order of Saint Stephen.

Picture(s):

1 The Corvin Chain awarded to Klebelsberg, the proposer of the award

2 The Corvin Wreath and the Corvin Badge

3 The recipients of the Corvin Chain and Wreath in the reception hall of the Buda Castle | Unknown photographer, 14 February 1931

HONOURS

Klebelsberg's work was recognized by both his Hungarian and international contemporaries. During the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, he was awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of Franz Joseph, and in the year of its founding, Klebelsberg received the Corvin Chain. Additionally, several cities in Hungary, such as Sopron and Kecskemét, granted him the title of honorary citizen.

He was also honoured with numerous foreign state awards, including those from Greece, Finland, Italy, and Sweden, which he wore with pride on festive and significant occasions. Today, much of his collection of awards is preserved in the Coin Collection of the Hungarian National Museum.

Picture(s):

1 Klebelsberg (centre) during the inauguration of Minister Sándor Ernszt | Photograph by unknown photographer, 1930

2 Klebelsberg's honours:

Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown of Italy with Star | First Class Badge of the Order of Polish Rebirth

Swedish Grand Cross of the Order the Star of the North with Star | Finnish Grand Cross of the Order of the White Rose with Star

Magistral Grand Cross of the Order of Malta, Second Class

HIS MEMORY

Klebelsberg passed away unexpectedly at the age of 57 in 1932. After his death, a memorial exhibition was held in his honour at the Budapest Museum of Fine Arts in 1933. In 1934, the historical institute within the Collegium Hungaricum in Vienna adopted his name. In 1939, a public statue was erected in the Pest city centre, which today stands on the Buda side in his memory.

In the decades following World War II, his name faded into obscurity. After the political changes in 1989, more attention was paid to his life and the results of his work. The University of Szeged Library adopted his name, and new public artworks were created. Streets, scientific and pedagogical scholarships were also named after him. Today, scholars in the humanities can continue their research in cities like Rome, Vienna, Berlin, or even London and Paris, with the annually awarded Klebelsberg Kuno Scholarship.

Picture(s):

1 A huge crowd accompanied the minister on his final journey in Szeged | Photograph by unknown photographer, 15 October 15 1932

2 Klebelsberg's statue in the Vienna Historical Institute | Photograph by unknown photographer, 1934

3 Klebelsberg's statue in the centre of Pest | Photograph by Alfréd Pobuda, around 1940